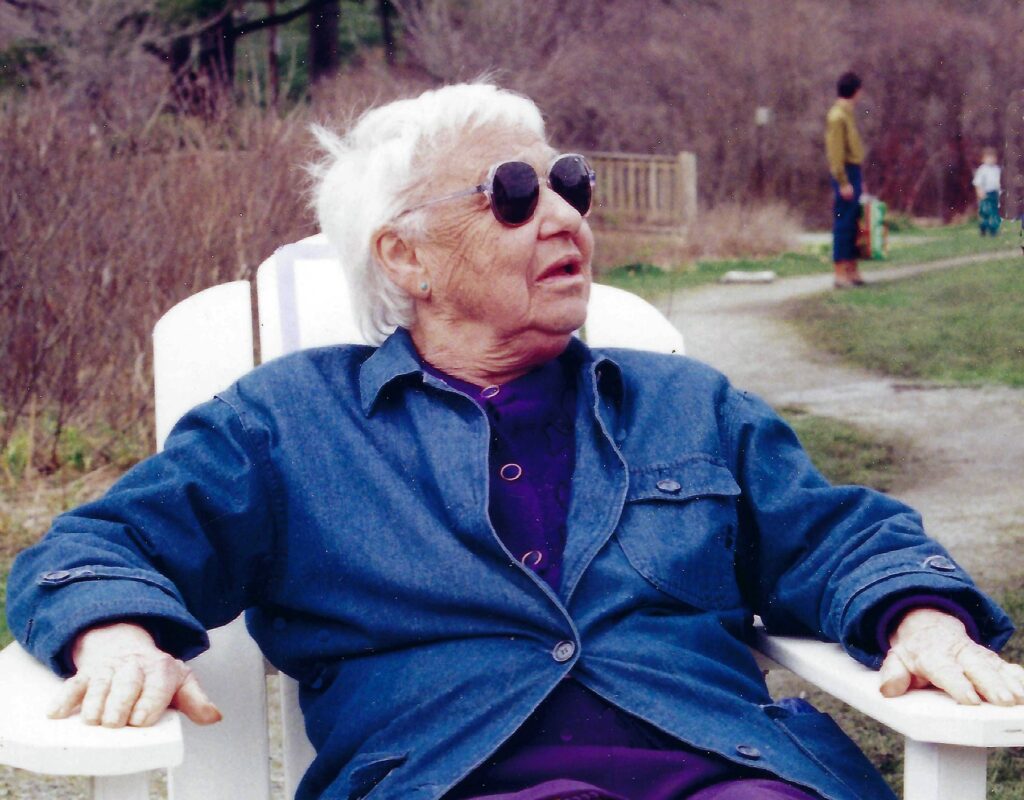

At their meeting on July 27, the Water Committee of Green Acton welcomed the daughter and granddaughter of Charlotte Sagoff to share memories of their influential foremother. In the 1970s and 1980s, Sagoff campaigned successfully to get industrial pollution from the W.R. Grace facility in Acton cleaned up, and in 1996 she organized the first Acton Earth Day.

Charlotte Sagoff’s granddaughter, Amelia Sagoff, moved to Acton four years ago, and is a founding member of Green Acton’s new Biodiversity Committee. She describes her work as “building innovative data products in the healthcare ecosystem.” Charlotte Sagoff’s daughter, Ruth Perry, is an emerita Professor of Humanities at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and lives in Cambridge.

The meeting also brought out other long-time Acton environmental activists Debra Simes, Debby Andell, and Carolyn and Andy Platt, with their own memories of the W.R. Grace struggle and the early Earth Day celebrations.

Early years

Ruth Perry recounted family lore about Charlotte’s pre-Acton life. Charlotte’s mother was a shop steward for the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union. Carried on her mother’s back, Charlotte was on the union picket line before she could walk. During World War II, Charlotte’s first husband, anthropologist Marvin Opler, was assigned to wartime service at the Tule Lake Relocation Center, an internment camp for Japanese Americans. Charlotte taught elementary school in the camp. On their days off, using their own money, Marvin and Charlotte bought and served milk and oranges for the children in the camp. After the war, Marvin Opler and the other social scientists stationed at Tule Lake publishedImpounded people: Japanese Americans in the Relocation Centers, describing the psychological and social effects of the incarceration. Ruth Perry emphasized how these early experiences underpinned Charlotte Sagoff’s activism during her Acton years. “She never thought that official channels could fix anything… she was a community organizer… It’s a lesson that everyone should learn.”

Charlotte moved to Acton in 1973 with her second husband, Maurice (“Maury”) Sagoff, a journalist and poet, best known as the author of ShrinkLits: 70 of the World’s Towering Classics Cut Down to Size.

New in town, Charlotte was frustrated because there was no food co-op — so she set out to found one. An oral history interview with Charlotte, recorded by Acton Memorial Library staff in 2000 and provided to the Acton Exchange by Ruth Perry, tells the tale in Charlotte’s own words: “I’d been a co-op minded person from the time I was a young girl. My mother lived in, I think, one of the first co-op buildings in New York City when I was about 13… Over 30 people showed up…for that first meeting… Two vans…from here [I] went down every Tuesday morning to Chelsea, to the produce market… I remember the biggest coup of all was one of our members… found avocados for six cents apiece… [There was] somebody who’s a cashier. Somebody who does the ordering. I’m the personnel manager because I know all the pieces of it and if somebody can’t come in … you’re supposed to notify me…I was the coordinator. I ran the whole thing.”

The library interviewer then asked about a poem she had found in the library collections, written by Charlotte and Maury about the food co-op. It’s included with the oral history, and begins:

‘Twas the night before Tuesday

And all through the house

Not a creature was stirring

Not even the spouse

who had set the alarm for 4:30 or

so she’d fall out of bed and be ready to go.

And so at the dawn’s very earliest peep

with eyes semi-closed and still half asleep

our buyers and drivers set forth once again

to wheel and to deal with the Marketing men.

Fighting to clean up the W.R. Grace site

The Green Acton Water Committee was most eager to hear about Charlotte’s role in the fight to get the site of the W.R. Grace chemical company cleaned up. As summarized on the Green Acton website, from 1945 to 1991, the American Cyanamid Company, the Dewey & Almy Chemical Company, and then W.R. Grace, Inc. produced sealants for rubber containers, latex products, plasticizers, concrete, and other products on the property in southeast Acton. Wastes were disposed of in unlined lagoons or placed into an on-site industrial landfill. In the fall of 1978 organic contaminants were discovered in municipal drinking water supply wells Assabet 1 and Assabet 2, and in December 1978 both wells were closed, cutting off 40% of Acton’s water supply.

At the time, both technical and governmental mechanisms to cope with industrial pollution were in their infancy. The pollution at Love Canal had been discovered just one year prior, in 1977, and it wasn’t until 1980 that Congress passed the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), commonly known as “Superfund.” When the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) established the initial Superfund National Priorities List in 1983, specifying sites for long-term remedial action, the W.R. Grace Site in Acton was on the list.

Community activism, with Sagoff in a leadership role, was essential in spurring government action toward cleaning up Acton’s industrial pollution. The EPA Oral History Project recorded an oral history interview with Charlotte in 2005, when she was 91. EPA’s interviewer asked about how Sagoff got involved with the W.R. Grace cleanup and the role of the organization she co-founded, Acton Citizens for Environmental Safety (ACES). In her own words: “I had been a biology teacher at both a high school and college level. So I was aware. I understood the lingo. I was aware of what was going on in other places …. the stench was enormous … not from the new well, but from the old well … I was on the Board of Health, so the issue came up there. Or I brought it to them … It was in 1979 that I convinced the Board of Health that they needed to turn to EPA on this issue. And we started this organization, ACES, in 1979. … we were talking about the issue … standing in the parking lot of Town Hall after a Board of Health meeting. And I said, ‘Well I live down the street.’ It was cold, it was October, so I said, ‘Why don’t we continue this at my house?’ And that’s when we started, without a name or anything … [ACES evolved into] a large group. At one point, I thought we needed money to do some lab work on determining what the exact substances were. I asked people to send in $10 fees — dues to ACES — and I got $4,000.”

The interviewer also asked about the reaction around town: ” … people in Acton were all extremely sympathetic with ACES and helped whenever necessary … The Selectmen would talk about it occasionally. … Well, people in real estate didn’t like it just because they thought it would be difficult. Even though schools were good, the water was bad! But our Water District was immediately set to cleaning it.” The Acton Water District affirmed the role of community citizen activism in their 100th anniversary brochure: “It was initially neighborhood residents who initiated alerts to Town and District officials. These Actonians formed an activist citizen organization called ACES (Acton Citizens for Environmental Safety). They began to assemble resources from their ranks and from friends in the region. They found technical resources, political support, and provided active monitoring of the W.R. Grace Manufacturing Plant in South Acton. This involvement was eventually welcomed by Town and District officials as the severity of the contamination and needed resources became evident.”

The EPA interview also emphasized the role of local journalism: “[O]ne of my major techniques was to see to it that every issue of the weekly newspaper that came to Acton, called The Acton Beacon, had stuff about the water and stuff about treating, looking, exploring, fighting with Grace. It was there every week…. [At meetings] I would always sit down next to the reporter.” The Acton Beacon ceased publication in 2022.

After learning about Charlotte’s work on the W.R. Grace situation, Green Acton meeting attendee Andy Platt, who studies organizational leadership, summed up Charlotte’s approach, with implications for today: This woman was incredible in her fearlessness and focus, expertise, and data focus. She “de-siloed” the town, got the different groups to talk together. And, in Andy’s view, that grass roots activism is still alive in town today, especially in environmental stuff.

Debra Simes and Debby Andell recalled a “Charlotte’s Web” of contacts throughout the town. “The house on Main Street was a central location, and they built a room on the back porch, always with a petition on a clipboard; the back door always open.”

Cleanup of the W.R.Grace Superfund site continues today. The most recent report on the site and a public information session held at Acton Town Hall in November 2024 show that the groundwater is very much cleaner than when remediation began, but contamination levels still exceed the target cleanup levels spelled out in the Record of Decision. The South Acton Water Treatment Plant, built in part with money from W.R. Grace, continues to treat Acton’s drinking water for the contaminants that ACES railed against. Green Acton and ACES merged in 2016. The Green Acton Water Committee continues the work of ACES, most recently by submitting detailed comments to EPA on Grace’s draft 2024 groundwater monitoring report.

Acton Earth Day and beyond

People who arrived in town too recently to remember the W.R. Grace struggle are more likely to remember Sagoff as the organizer of the first Acton Earth Day, held at the Acton Arboretum in 1996. In the library’s oral history, Charlotte recounts: “In ’90 I had gone to the Earth Day in Cambridge and … wondered … why can’t we do it here in Acton? … People loved it. People said, ‘Oh, this is like the sixties.’”

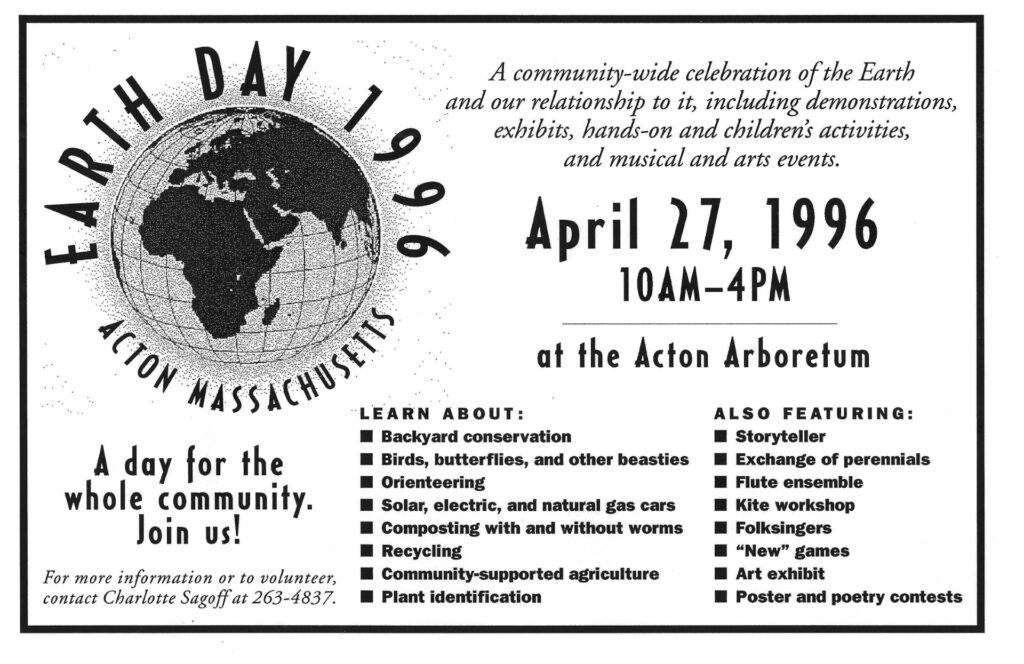

Debby Andell still has a stack of binders filled with photos, news clippings, announcements, letters, and to-do lists documenting the huge effort that Sagoff and her collaborators invested in organizing the early Acton Earth Days. As shown in the announcement below, the first Acton Earth Day, 29 years ago, foreshadowed many environmental topics that are still on Acton’s environmental agenda: backyard conservation, pollinators, composting, recycling, alternative energy cars, community supported agriculture. The approach was more celebratory than doom-and-gloom or science-laden, featuring storytelling, music, art, poetry, flowers, and games. And note the fine print: “For more information or to volunteer, contact Charlotte Sagoff.”

Charlotte Sagoff died in 2007. Her successor as president of ACES, Mary Michelman, wrote in tribute, “I am always aware of how lucky Acton is to have had Charlotte leading the charge to hold Grace accountable; and to make the Town, Acton Water District, the Commonwealth, and EPA pay attention and take action. I inherited the easy end of the fight. She fought the early, difficult battles. Charlotte made it impossible for W.R. Grace, (or anyone else), to get away with brushing off the fact that Grace had polluted Acton’s drinking water supply and needed to clean it up.” After her death, friends and grateful townspeople designated and raised funds for the Charlotte Sagoff Memorial Garden, located outside the main entrance of the Acton Memorial Library. The word bricks in the pathway include “love,” “laugh,” “read,” “sing,” “question,” and “persevere”. The inscription on the central block table says, “DO THE RIGHT THING.”

If you remember Charlotte Sagoff, or the fight to get the W.R. Grace pollution cleaned up, or the early Acton Earth Days, consider sharing your memories with the Acton community in a letter to the Acton Exchange.

Kim Kastens is an Associate Editor for the Acton Exchange and the chair of the Green Acton Water Committee.