Juneteenth: Acton commemoration brings speakers and crowds

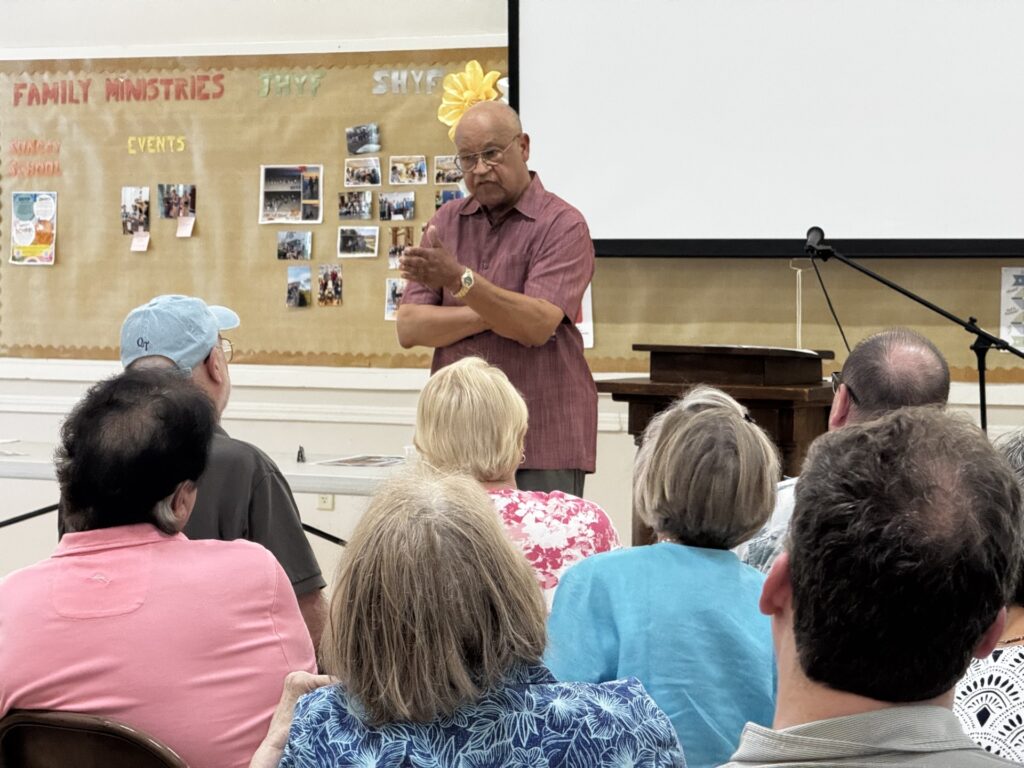

On June 19, Acton’sDiversity, Equity, and Inclusion Commission held its first official commemoration of Juneteenth. The multi-part event started at the Acton Congregational Church with a presentation by local authorRay Anthony Shepard, who explored the history of Juneteenth and its connection to broader struggles for freedom.

The event continued at the (thankfully air-conditioned) Acton Woman’s Club, with speakers Amy Cole and Diane Randolph Johnson presenting.

Ray Anthony Shepard Challenges Acton to Unpack the True Meaning of Juneteenth

By Greg Jarboe

Shepard said his biographies offer young readers a compelling and more accurate perspective on race in American history than earlier texts. A former history teacher and textbook editor, he now writes the kinds of books that were not in his classroom and that he wasn’t able to publish during his editing career.

Shepard illuminated the historical significance of Juneteenth, transforming what might be considered dry facts into an engrossing narrative for the “young at heart.” Speaking to approximately 80 people, Shepard challenged his audience to reflect on the deeper meaning of this national holiday, urging them to remember at least 10% of his words despite the absence of visuals.

Shepard opened by posing thought-provoking questions about the paradox of “the unfreed in the land of the free,” the immense sacrifice of soldiers in the Civil War, and the subsequent re-enslavement and ongoing struggle for civil rights. He also questioned the practice of hyphenating Americans, suggesting it implies varying degrees of American identity.

He then delved into the historical event of June 19,1865, when Union General Gordon Granger read General Order No. 3 in Galveston, Texas, officially ending slavery in the last Confederate state. Shepard emphasized the order’s declaration of “absolute equality of personal rights, and rights of property between former enslavers and enslaved people.” This moment, he stated, triggered a “jubilant celebration – a jubilee of a vision for their future.”

Shepard stressed that emancipation was not a simple proclamation but was achieved through the “blood of the enslaved, by Black and white abolitionists, and by the blood of Black and white Union soldiers.” This profound sacrifice, he noted, is why red foods are a mainstay of Juneteenth feasts. He shared an excerpt from his book, Now or Never! 54th Massachusetts Infantry’s War to End Slavery, highlighting the courage of Black soldiers, particularly the 54th Massachusetts, who fought and died without pay, due to unequal wages.

He articulated the vision of America that the newly freed believed in, quoting conservative columnist David Brooks: “America stands for a set of universal principles: the principle that all are created equal; that they are endowed with inalienable rights; that democracy is the form of government that best recognizes human dignity; that best honors beings who are made in the image of God.” However, Shepard acknowledged that this vision faced opposition from former slaveholders and those who believed in race-based human hierarchies.

Despite that opposition, Juneteenth celebrations persisted, moving to Black churches and eventually leading to the establishment of emancipation parks in a number of locations. The tradition spread northward during the Great Migration. While largely unknown to most Americans for many years, Juneteenth became a Texas state holiday in 1980 and, in 2021, largely due to the efforts of 89-year-old Opal Lee, it was declared a national holiday.

Shepard drew a parallel to Frederick Douglass’s 1852 question, “What To The Slave Is the Fourth of July?” He echoed Douglass, asking, “What to America is Juneteenth?” He then presented a sobering list of contemporary actions that he finds “hideous and revolting” and believes “trash the vision of Juneteenth,” including the detention of long-term residents, raids on businesses and immigration centers, and discriminatory refugee policies. He also cited the dismissal of the first woman and Black librarian of Congress, and the replacement of a four-star general for recognizing Black patriots. Shepard attributed these actions not to individuals but to voters and neighbors who continue to support such policies, noting that 19% of Acton residents voted for the current president and his policies. He stated these actions harken back to the Jim Crow era and even to Hitler’s Brown Shirt squads.

Addressing the common misunderstanding of Juneteenth, Shepard challenged the “false narrative” that suggests racial correction was unnecessary and that America has always been a perfectly shining nation. He argued that hiding achievements in racial progress, such as the efforts to end slavery and secure civil rights, makes children uncomfortable and less patriotic. Shepard asserted that Juneteenth represents the “unraveling of a caste labor system” and the achievement of a moral principle: the end of American slavery in the last slave state.

He then highlighted “hidden facts” from American history, such as the significant presence of Black and Brown patriots in the Revolutionary Army and the fact that George Washington and eleven other presidents were enslavers. Shepard contended that the current call for “truth and sanity in American History” is a “whitewashing” effort to “stifle the pursuit of our founding principles and cloud the vision of Juneteenth.” He described it as an attempt to restore an “ancient empire concept” where people are governed by “betters based on heredity, gender, religion, and ethnicity,” explaining the renewed urgency to ban books and dictate educational content.

Shepard concluded by emphasizing that Juneteenth, like Memorial Day and July 4th, commemorates America’s progress toward “the universal principle of liberty and equality.” He urged his audience to “stay awake, be WOKE,” and resist “false narratives”. He ended with lines from his book, A Long Time Coming, posing the perpetual challenge of agreeing “who the ‘we’ should be in ‘We the People.’”

Shepard’s talk was followed by a participatory sing of “Lift Every Voice and Sing” by James Weldon Johnson.

After Shepard’s talk, most of the audience made the short walk to the Acton Woman’s Club, where local tour guide Amy Cole shared stories about Emancipation and Acton’s abolitionist history. The commemoration concluded with a reflection on the role of horse culture in the history of Black freedom via Zoom by Diane Randolph Jones.

Echoes of Freedom: Acton’s History Resonates on Juneteenth

By Greg Jarboe

After Mr. Shepard’s presentation, the audience walked around the corner to the Acton Woman’s Club which hosted Amy Cole, who gave a compelling Juneteenth talk. Cole delved into Acton’s rich history of emancipation and the efforts of local abolitionists, drawing connections between the Revolutionary War and the Civil War.

Cole began by providing context on the history of slavery in Massachusetts, noting it was the first British colony in North America to legalize slavery, in 1641, following the Pequot War, that led to the enslavement of both Indigenous people and Africans.

The central theme of Cole’s presentation was the continuity of the fight for freedom from the Revolutionary War through the Civil War and beyond. She highlighted that colonists used rhetoric comparing themselves to enslaved people during their struggle against British rule. This discussion of freedom, in turn, inspired enslaved individuals to seek their own liberty.

Cole shared the poignant story of John Jack, the first enslaved man in Concord to secure his freedom. His headstone’s epitaph was written by Daniel Bliss — a Tory and brother-in-law to enslaver Reverend William Emerson — which underscores the contradictions and hypocrisy of the era. The pursuit of freedom by individuals such as Quock Walker and Elizabeth Freeman, who successfully sued for their freedom in “freedom suits,” contributed to the gradual end of slavery in Massachusetts by 1783.

A powerful illustration of this “bridge to freedom” was the Robbins family of Concord, now associated with The Robbins House. The family’s journey began with Caesar Robbins, born enslaved in Chelmsford. He fought in both the French and Indian War, with his enslaver receiving his pay, and later in the Revolutionary War under Captain Israel Heald of Acton, earning his freedom through military service. Caesar’s daughter, Susan Garrison, became a co-founder of the Concord Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1837, the only woman of color in the organization.

His granddaughter, Ellen Garrison, emerged as a trailblazer for human rights. A scholar who attended Concord public schools, Ellen dedicated herself to educating formerly enslaved people, teaching them to read and write, a right they had been previously denied. Nearly a century before Rosa Parks, Ellen challenged the legality of segregation under the Civil Rights Act of 1866 when she and another Black teacher were forcibly removed from a “whites only” waiting room in the Baltimore train station. Although her lawsuit against the railroad official was ultimately dismissed, Ellen’s determination to fight for her own rights and the rights of others continued, extending her grandfather’s fight for freedom.

Cole then shifted focus to Acton, detailing the significant divide within the local church between Unitarians and the orthodox body. Reverend Marshall Shedd, Acton’s minister from 1820-1831, sold property to construct a chapel in 1829 for the more conservative members, a building known today as the Acton Woman’s Club. Both groups had previously met in the 1807 meetinghouse, currently the site of the Town Hall. Another parcel of land was sold to Dr. Harris Cowdrey, a conservative church member and ardent abolitionist, who built his home in 1830 at the corner of Nagog Hill Road and Main Street. Cowdrey was a member of the Middlesex County Anti-Slavery Society, and his house later served as the home of the Acton Woman’s Club before their current location.

Reverend James Trask Woodbury became the first minister of the newly formed Evangelical Society in 1833, after the church’s split. This society would later build a church on the site of the current Acton Congregational Church. Woodbury was a prominent abolitionist and supporter of the Temperance Movement, also a member of the Middlesex County Anti-Slavery Society. His anti-slavery stance was well-documented in publications such as William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator. Woodbury notably refused to allow enslavers in his church, invited anti-slavery speakers, and spoke at various anti-slavery gatherings.

However, a feud developed between Woodbury and Garrison when Woodbury objected to Garrison’s support of the Grimke Sisters, who were on the anti-slavery circuit. Woodbury disapproved of the mixed-gender audiences they attracted and firmly believed women should not speak publicly on reform issues. Ironically, the Grimke Sisters had inspired the founding of the Concord Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1837, which included many prominent women such as Mary Merrick Brooks, and Cynthia Thoreau and her daughters, Helen and Sophia. Mary Merrick Brooks, quoted in “The Liberator,” powerfully connected the fight for freedom, stating, “Make it manifest that the descendants of those who so bravely resisted British oppression in 1775 are not only alive but awake too on the great subject of human freedom.”

The feud between Woodbury and Garrison intensified, playing out openly in “The Liberator,” as Woodbury disliked Garrison’s criticism of societal and governmental structures, including the church. The conflict came to a head at an Acton meeting on July 23, 1839, when a vote to grant women voting rights in the Middlesex County Anti-Slavery Society passed, leading Reverend Woodbury to storm out, though he continued his fight against slavery.

Cole also touched upon the 1851 Acton Town Meeting resolutions in response to the federal Fugitive Slave Act. These resolutions referred to the Revolutionary War as a continuation of the fight for freedom, making clear Acton’s opposition to the act and requesting their position be published.

Reverend Woodbury was instrumental in securing funds for the Davis Monument and was friends with Hannah Davis, widow of Captain Isaac Davis, who gave him the shoe buckles her husband wore on April 19, 1775. The Davis Guards were named in memory of Captain Isaac Davis. Daniel Tuttle, Captain of the Davis Guards, initially believed the South had the right to hold slaves if they remained loyal to the Union. However, the attack on Fort Sumter was seen as an act of treason, prompting him to lead the Guards to Washington to protect the capital.

The Davis Guards, part of the Massachusetts 6th Regiment, were the first Union regiment to encounter hostile action and suffer the first casualties of the American Civil War during the Baltimore Riot on April 19, 1861, exactly 86 years after the Revolutionary War began in Lexington and Concord.

In a lasting tribute, Acton native William Allen Wilde donated the Acton Memorial Library to the town in 1890, in memory of the soldiers and sailors who fought in the Civil War. Today, the library houses both Revolutionary and Civil War exhibits. In 1893, Reverend Woodbury’s children presented Captain Isaac Davis’ shoe buckles, which had been given to their father, to the library.

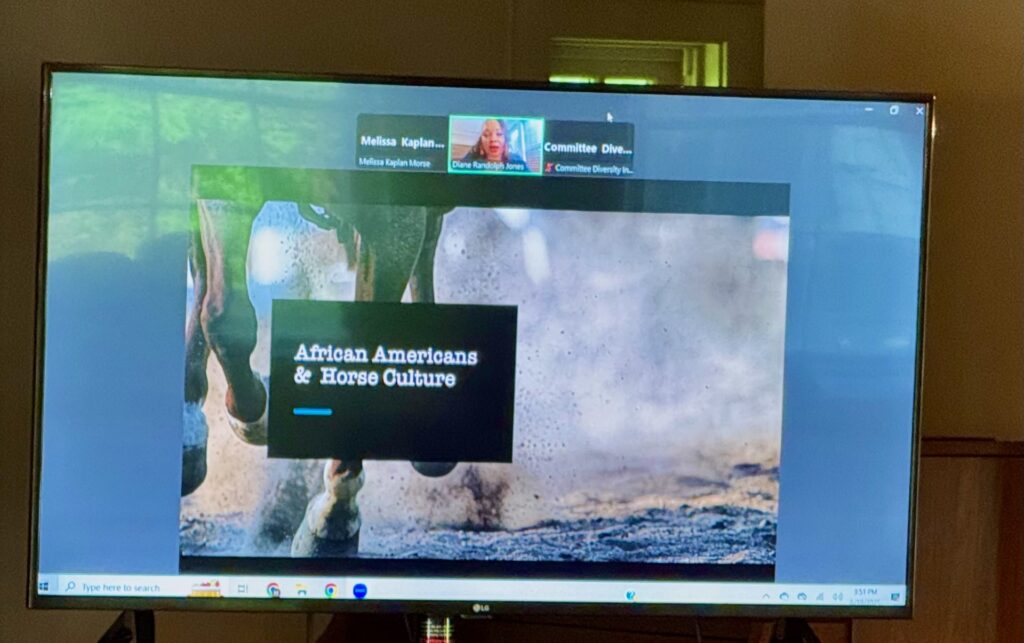

African Americans and Horse Culture: Adding historical context

by Miriam Lezak

After Amy Cole’s presentation, Acton resident and DEI Committee member Diane Randolph Jones joined the meeting by Zoom to discuss horse culture as part of the African American experience.

Randolph Jones started her talk by mentioning that she and her daughter are both avid horse riders but, as Black women, they stand out, at least in this part of the country. She then dug into some of the history of Black people and horsemanship.

In the antebellum South, enslaved men often took care of the horses, including grooming and training. After the war, many of these men continued to practice and hone their skills. In the first Kentucky Derby, held in 1875, 13 of the 15 riders were Black, and Black jockeys won the Derby for its first six years. As the Kentucky Derby and other races gained prominence, the number of Black riders dwindled. However, horses are still trained by Black riders in the south and elsewhere.

In the meantime, the call of the wild West was heard by many, including Black men and women. Although you would never know by watching Western-themed movies and shows, fully a quarter of cowhands were Black. While working in the West brought opportunities, racism still abounded. Indeed, the words “cowboy” and “cowgirl” were reserved for Black riders, while white riders were referred to as “cowhands.”

While Randolph Jones was not in person at the Woman’s Club, she had sent a beautifully worked saddle, girth, and a horseshoe, to represent some of the skills that were practiced by Black craftspeople.

After the day’s events concluded, Leela Ramachandran, the vice-chair of the Acton-Boxborough Regional School Committee, was asked to share her thoughts about Shepard’s question, “What to America is Juneteenth?”.

She thought quietly for a moment and then asked: “If the Civil War freed the unfree, then why was the Civil Rights movement needed?”

Greg Jarboe writes on a variety of topics for the Acton Exchange. He is a former editor of the Acton Minuteman and a former chair of the Acton Select Board, and a current member of the Acton Finance Committee, Public Works Facility Committee, and the Economic Development Committee.

Miriam Lezak is an associate editor for the Acton Exchange, an Acton Memorial Library Trustee, and an occasional writer for the Exchange.