On Jan. 10, 2026, residents from Acton and beyond gathered at the Acton Memorial Library to commemorate the 250th anniversary of Thomas Paine’s groundbreaking pamphlet, “Common Sense.” The meeting room was full, although many had sent their regrets as they set out to join protests. The timing felt almost prophetic. The journey to the library that afternoon took this writer through Bolton Center, past “No ICE” protests, a reminder that the questions Paine wrestled with — about authority, governance, and the rights of citizens — remain relevant today, at the five-year anniversary of the attack on the U.S. Capitol and with recent events in Venezuela and Minneapolis.

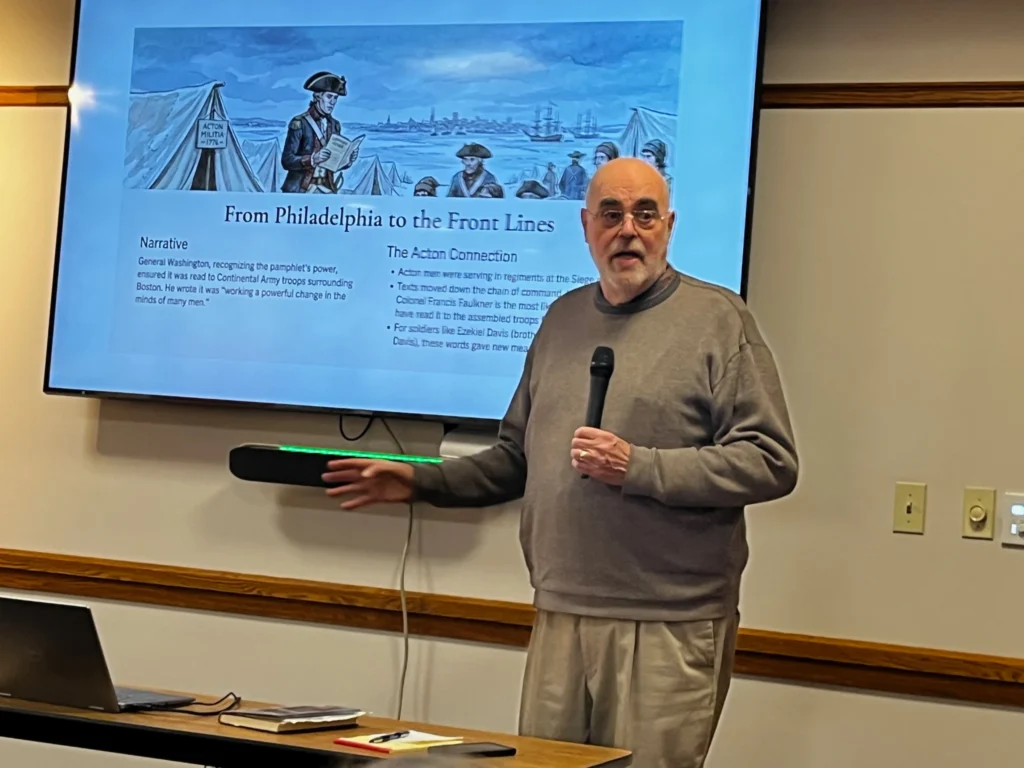

The speaker was Acton resident and journalist Greg Jarboe, who studied comparative colonial history at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. (Disclosure: Jarboe is a frequent writer for the Acton Exchange.)

Jarboe painted a portrait of Thomas Paine as history’s least likely revolutionary. With an education that ended at age 13, multiple business failures, and a string of personal tragedies including the death of his first wife in childbirth and the departure of his second, Paine was, by age 37, unemployed and wandering the streets of London. Then came a chance encounter with Benjamin Franklin that would change history. Franklin suggested Paine try his luck in Pennsylvania. There, Paine became editor of Pennsylvania Magazine, writing on a wide variety of topics under multiple bylines to create the impression of a full staff.

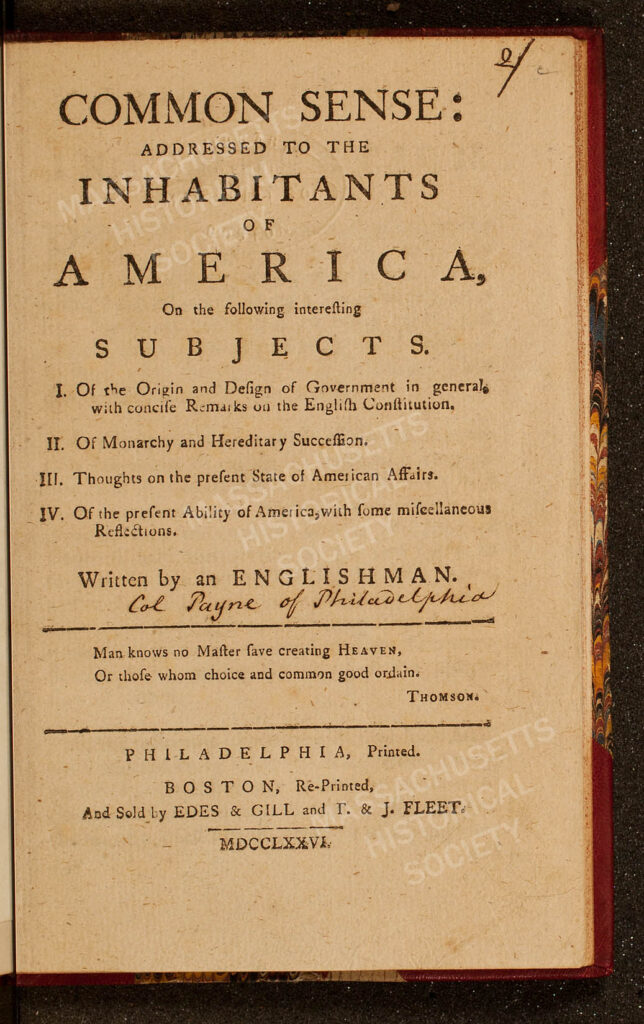

Jarboe emphasized a crucial point often overlooked in history: timing is everything. On January 9, 1776, news reached the colonies that the British had rejected the Olive Branch Petition. That petition, written the previous July after the Battle of Lexington and Concord, had forgiven the British and sought reconciliation. What had been a “family quarrel” about “the rights of Englishmen” suddenly became something else entirely with the rejection of the Olive Branch Petition. When “Common Sense” appeared on January 10, the colonies were primed to hear its message. The timing transformed a philosophical argument into a call to arms.

Jarboe explained that Paine’s pamphlet contained four essential arguments that “changed America.” First, he established that government is a necessary evil, distinguishing between society and governance. Second, he weaponized the Bible, the colonies’ best-selling book, to argue that monarchy itself contradicted God’s will. Third, he made the practical case for separation: your father doesn’t shoot at you. Fourth, he addressed feasibility: Americans had the trees to build ships, the dollars to finance an army, and the economic foundation to win.

His most revolutionary statement challenged centuries of political thought: “In America, the LAW is KING!” The pamphlet’s slogan became a rallying cry: “The blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature cries — ’tis time to part”.

The message of “Common Sense” achieved what today might be called viral status. From Philadelphia to the front lines, 120,000 copies reached a population of 2.5 million. It was published in newspapers, read aloud to soldiers and congregations, and debated in taverns across the colonies. Paine’s informal writing style suited the oral tradition. In an era of low literacy rates, the message spread rapidly through word of mouth.

Jarboe connected “Common Sense” to Acton’s own history. While official minutes from the Historical Society and minuteman companies don’t record it, Jarboe suggests that “Common Sense” would surely have been read aloud in Acton, perhaps at Jones’ Tavern. In Boston, Acton’s soldiers may have heard “Common Sense” read by Lieutenant Colonel Francis Faulkner, the senior officer directly responsible for the regiment containing Acton men.

On June 14, 1776, Acton’s town meeting minutes recorded a call for an American Republic, pledging “lives and wealth” to support it, predating the more famous Declaration of Independence signed on July 4. Once again, Acton was ahead of its time.

Jarboe highlighted an interesting philosophical tension that emerged from “Common Sense”. Thomas Paine held an optimistic view of human nature and believed in government directly from the people. John Adams, less optimistic about human nature, advocated for government with checks and balances. The Constitution that ultimately emerged mirrored “Common Sense” in its basic tenets, while incorporating Adams’s cautionary wisdom.

Jarboe mused about how the message of “Common Sense” would have been conveyed in 2026: Would it be a pamphlet, a podcast, a viral tweet thread? Is it the message or the timing that matters most? Exploring this question, Jarboe shared a video that an audience member, a history buff from Bedford, Jerry Skirula, had created with the help of Jarboe and AI tools, expressing modern messages with the same spirit as “Common Sense”. Skirula had been inspired to work on the modern-day version after visiting the site in Philadelphia commemorating “Common Sense”.

The answer to the question of message vs. timing, as Jarboe demonstrated through Paine’s story, is both. The right message at the right moment can change everything. But it requires courage to speak plainly, wisdom to understand the moment, and faith in the capacity of ordinary people to grasp profound truths. On January 10, 2026, in a library in Acton, Massachusetts, the audience was reminded that the questions Paine raised 250 years ago remain our questions still: Who governs? By what authority? And when tyranny threatens, what will we do about it?

For those who missed the talk, the full presentation is available at ActonTV: “Common Sense” and the Birth of Independence.

Ann Marie Testarmata, MD, has turned her attention from medicine to the community, writing for the Acton Exchange.

Editor’s note: The AI tool Claude was used in creating the first draft of this article, using the notes of the author.