Jan. 28, Francis Faulkner Meeting Room, Acton Town Hall: Historian Alexander Cain, JD, tonight brought to light the typically untold stories of Boston’s civilians caught in the crossfire at the dawn of the American Revolution. Mr. Cain’s presentation, “I Screamed with All My Might”-The Civilians Trapped Behind the Boston Siege Lines”, was one in a series of events in Acton’s 250, Beyond the Bridge series.

After an introduction by Acton 250 Chair Pam Lynn, Mr. Cain began his slide show with the battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775. Most residents thought the British were out to seize Samuel Adams and John Hancock, but their real target was a supply depot in Concord. After hearing about the Lexington battle on April 19, fear and panic gripped many Bostonians, and they were well-founded. British General Gage, of the Massachusetts Grand Army, ordered a lockdown of the city of Boston, forbidding anyone from entering or leaving, fearing that they would supply weapons to the rebels. Since there was only one way in or out at the time, Boston Neck, the lockdown was easy to enforce.

On April 22, the residents, seeing their provisions dwindling fast with no access to the outside world, drafted an appeal to the general to evacuate to the countryside. After a tense meeting, Gage agreed, provided they left their weapons behind. However, this was not a smooth evacuation, as the general reversed himself and ordered all residents back to the city, only to change his mind again on the 27th and open Boston Neck once again. But Gage’s subordinates undermined his orders, requiring people to obtain passes to travel, which were not easy to get.

The siege resulted in a crescent-shaped blockade extending from Charlestown to Braintree, with about 7000 people serving as human shields for General Gage. The economy collapsed and food was scarce. Timothy Newell claimed he was invited by two friends to dinner; on the menu: rats. And, in the cold winter of 1776, heating fuel was hard to find. Civil liberties were violated, as men were forced into manual labor, and houses of worship were leveled for fuel or turned into riding stables. And there were accounts of the soldiers plundering residents’ property, helping themselves to all the liquor they could steal and leaving houses trashed in their wake.

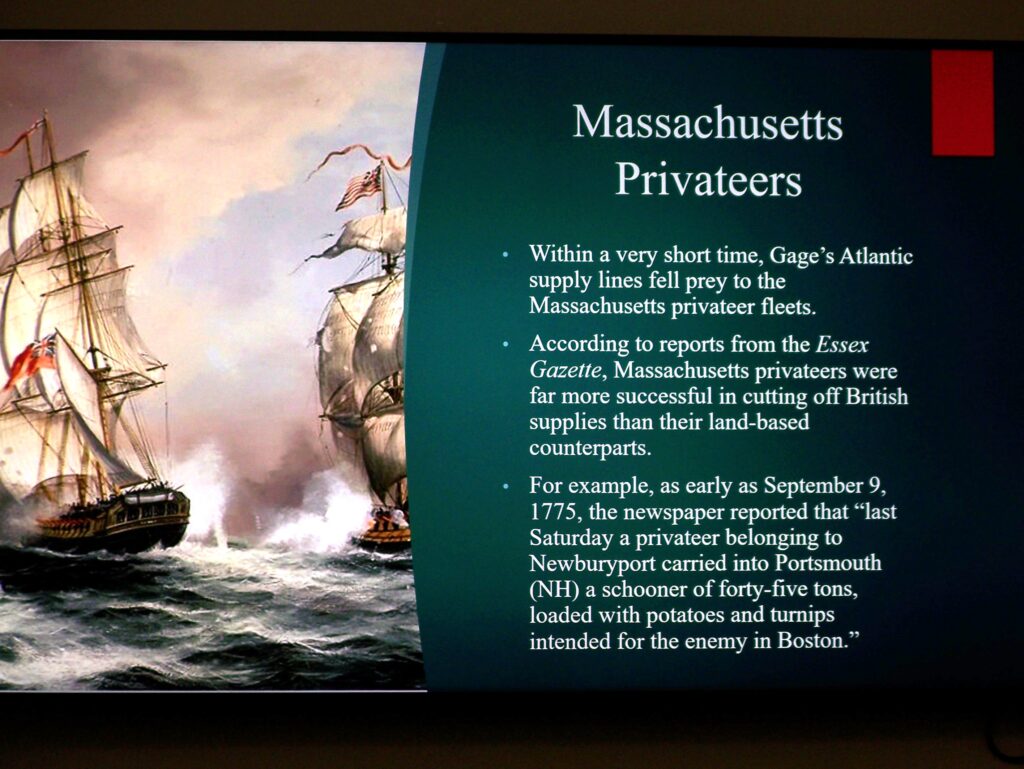

In response, the colonists launched a series of raids to seize supplies from the Boston islands. This forced Gage to use supply lines from Nova Scotia, the West Indies, and even England. The Massachusetts Committee on Safety utilized mariners on the North Shore and Plymouth to break the Brits’ grip on Boston. Privateers on the sea proved to be key in turning the tide, as these ships were much more successful in cutting off the British supplies than the land forces.

Several of Mr. Cain’s slides showed the emotional writings of of ten-year-old loyalist Dorothea Gamsby, who wrote, “…At length one who stood conspicuously above the rest [Prescott] waved his bright weapon, the explosion came attended by the crash, the shrieks of the wounded, and the groans of the dying. I screamed with all my might.”

As if that weren’t enough, smallpox then took hold in Boston. It had arrived in New England in the early 1600s, with a devastating effect on Native Americans. In December, 1775, a British General Order pushed for inoculating all willing soldiers. General Gage sent a ship of three hundred people to several nearby seaports, but not for their freedom. Many historians think Gage sent those civilians, who turned out to be infected, to ease the burden of caring for them. But historian Anne M. Becker argued that his real aim was to spread the infection among the rebel troops, as a form of biological warfare. In a letter to John Hancock, General Washington asserted that the British were doing just that by administering vaccines to their troops, so he preferred no vaccines for his own men.

In March of 1776, the British ordered their troops to evacuate the city. But the residents had to endure a final round of pilfering and plundering homes and businesses by the exiting invaders. The British troops were even suspected of committing arson. John Rowe wrote, “There was never such destruction and outrage committed any day before this…the inhabitants are greatly terrified and alarmed for fear of greater evils.” When the American troops entered Boston, they were greatly welcomed as liberators as the siege ended. General Washington expressed his disdain for the invaders in a letter to his family, saying one or two Loyalists had already done what he hoped would have been a greater number: committing suicide.

To try to recover from their losses during the siege, many Loyalists and Patriots asked for compensation from the Continental Congress and the Massachusetts government. Some were paid, while others were not. After several weeks, the American troops moved to New York City, and Bostonians were spared any more occupations for the remainder of the war.

The next event in the Acton 250 series will be ” Henry Knox’s Trek from Ticonderoga: Myths, Realities, and Results for Boston” with J.L. Bell, on Feb. 26. For the rest of the schedule, see actonma.gov/250.

James Conboy writes for the Acton Exchange on a wide variety of topics.